Survey for the Maryland Native Plant Coalition

Tag: native plants

You Just Can’t Hack It: Correct Pruning for Healthy Trees

by Adreon Hubbard

On my walks through the neighborhood, I’ve noticed street and yard trees with various issues that might have been prevented through correct pruning. Our trees are subjected to many stressors beyond our control, but pruning when a tree is young is something the average person can do (even an arthritic retiree such as myself) to help the tree withstand these threats and live a longer, healthier life. Pruning also provides a fun outdoor workout and sense of accomplishment. Having just completed my TreeKeeper Pruning Certification, I am excited to share some tips and tricks. Even if you prefer to hire someone to prune your trees, knowing the basics can help ensure that you hire a competent professional and not a “hacker.”

Know when to prune, and keep safety in mind. The best time of year to prune most trees is generally thought to be in the dormant season, especially late Winter through early Spring. Pruning just before the flush of new growth allows trees to seal off their wounds rapidly. You can also see the branch structure clearly before leaf out, and there are fewer pests and diseases waiting to attack the wounds. Elms and oaks should only be pruned through February, however, due to their susceptibility to Dutch Elm and Oak Wilt Disease. Avoid pruning after severe drought. With that said, most trees can be safely given a light pruning at any time of year.

Wait two-three years after planting your tree before pruning it to allow for proper root establishment, but don’t wait until the tree is so large you can’t reach the branches with a pole pruner while standing on the ground. Tree climbing, ladders, power tools, and removing branches larger than 4” in diameter or close to power lines are best left to the professionals!

Know your reason for pruning. The interrelated goals of human safety, tree health, and aesthetics are the main reasons for pruning. Weak branch connections caused by poor structure may cause branches to break off in storms, leaving a jagged tear which opens the tree up to disease and decay. Healthy tree structure reduces such risks and tends to look balanced and attractive. Before pruning, spend some time carefully observing the tree from different angles. Ideally, do this with a friend to have a second set of eyes on it. You cannot put back a branch once it is cut, so “less is more.” Pruning is recommended in order to:

- Remove a second trunk or branch competing with the dominant trunk (certain species, such as SweetBay Magnolias, can be allowed to have multiple trunks)

- Remove dead branches or stubs

- Remove or shorten crossing, rubbing branches

- Remove or shorten nuisance branches in the street or sidewalk

- Remove branches with a V-shaped union (weak attachment)

- Thin the crown to increase light penetration and air flow

- Remove basal sprouts (“suckers”) or water sprouts

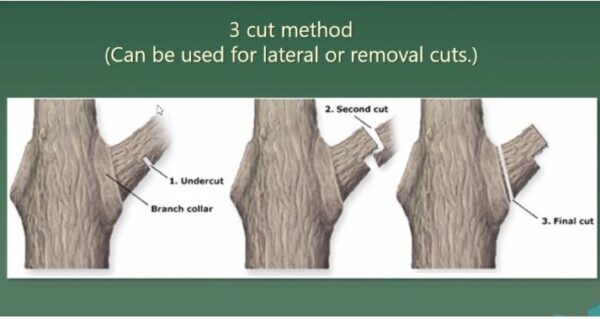

Know where to make the cut. Every cut causes a wound to the tree that never completely heals. Instead, the tree seals off, or compartmentalizes, the wound by making a callus around it. Arborists call this C.O.D.I.T.: Compartmentalization of Decay In Trees. Incorrect cuts lead to poor wound closure, leading to decay and infection. Look for the swollen part of the branch or trunk where the branch is coming out. That swollen area is called the branch collar and contains special cells that seal off the wound effectively. Always cut just beyond the branch collar in order to leave the branch collar on the tree. Use sharp, by-pass hand pruners, a pruning saw, or pole pruners for the cleanest cut. A clean cut will heal faster than a jagged cut, just like our skin heals faster from a paper cut than a gash. Use the 3-cut method for larger branches to reduce the risk of bark tear (see diagram.)

Don’t be a hacker: pruning practices that harm trees:

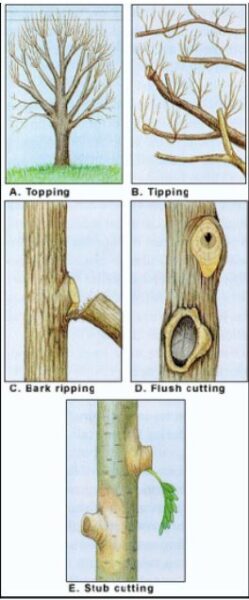

- Flush cuts: do not cut the branch flush with the trunk or parent branch–doing so will remove the branch collar and make the wound fail to close or close more slowly, leading to infection and decay.

- Stubbing: try not to leave a stub of the branch you are cutting. Be careful to cut just outside of the branch collar, but not too far outside of it. This can be tricky and take some practice.

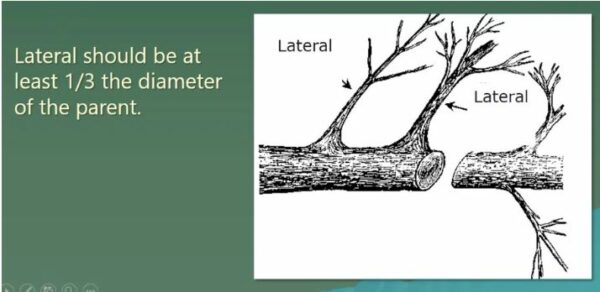

- Tipping: do not cut at a random spot on the branch just to shorten it. Branches should be cut just after a lateral branch one-third its size. Tipping causes the whole branch to die back and decay.

- Limbing up: do not cut the lower branches of the tree higher than one-third of the way up the trunk. It is especially important for young trees to retain their lower branches, because they help the tree trunk grow thicker and stronger.

- Topping/crown reduction: do not chop off the ends of the branches of a medium-large tree to reduce its size. This causes the tree to send up multiple water sprouts with weak branch connections in a frantic effort to produce leaves to feed the tree. It also creates large wounds that the tree is not able to seal off. Topping is an outdated, poor pruning technique no longer practiced by reputable arborists.

- Over pruning: do not remove more than 25% of the tree’s branches. Additional pruning can be done when the tree is older.

Next Steps: Feeling overwhelmed? I would be happy to visit your yard to give you tips (please email me at hubbardesol@gmail.com), and a neighborhood volunteer tree pruning demo and event is in the works for next winter. If you would like to learn more about tree pruning and planting and become part of a community of wonderful “treeple” who love trees, please consider taking the excellent TreeKeepers class run by TreeBaltimore of Baltimore City Rec & Parks. https://www.treebaltimore.org/treekeepers. It is free, open to county residents, and offered every Spring and Fall. Don’t have time for a class? The USDA Forest Service PDF HOW to Prune Trees is an excellent resource:, and there are helpful videos online, such as Ask an Arborist: The ABC’s of Pruning and 3 Step Pruning for Deciduous Trees. Thank you for caring for our community’s precious trees!

Sources:

Gilman, Edward: An Illustrated Guide to Pruning, 3rd Edition https://wwv.isa-arbor.com/store/product/24/

Adreon Hubbard is a certified Baltimore Weed Warrior and TreeKeeper, and a Maryland Master Naturalist and Master Gardener. She took all of the photos used in this article. The first two diagrams above are from a training PowerPoint from an online TreeKeeper class. The third diagram is from the USDA How to Prune PDF referenced in the article. This article originally appeared in the March 2023 issue of the Idlewylde Community newsletter, Idlewylde News. Adreon writes a regular nature column called In the Wylde.

Green Towson Alliance 2022 Year End Report

2022 was a banner year for Green Towson Alliance. We are pleased to have met many of our goals including planting trees in downtown Towson, helping community associations successfully plant native canopy trees in their neighborhoods, and cleaning trash out of our local streams that feed into the Chesapeake Bay.

Here’s what we accomplished in the past year:

TREES

In partnership with Blue Water Baltimore, GTA helped to coordinate the planting of more than 285 trees in Towson communities in the fall of 2022. Tree stewards worked with their neighborhoods to choose the right native tree for their yard or as a street tree. The vast majority of these trees are canopy shade trees which can grow at least 60 feet tall and provide much greater environmental benefits than the smaller, understory species.

MORE TREES! DOWNTOWN TOWSON TREE REPLACEMENT

72 trees were planted by Baltimore County in downtown Towson in December. GTA volunteers advocated for years for the replacement of trees that had died or been removed.The County has created a Street Tree Replacement Program that will add 1,300 trees in six concentrated areas. We are delighted that Towson is one of those areas that will benefit from this critical green infrastructure.

SAVING TREES AND OPEN SPACE

GTA volunteers worked with the Department of Environmental Protection and Sustainability (DEPS), the communities, and the developer of the Villas at Woodbrook (on the site of Villa Maria nursing home for the Sisters of Mercy on Bellona Avenue) to provide more open space, and to save a few more large specimen trees.

STREAM CLEAN-UPS

In partnership with the Alliance for the Chesapeake Bay, GTA organized 216 volunteers to pull 4,570 pounds of trash out of neighborhood streams in the spring of 2022. In many cases, volunteers also pulled invasive plants out of stream beds and the surrounding areas.

ADVOCACY FOR NATIVE TREES AND LOCAL PARKS

Green Towson Alliance testified at the Baltimore County Fiscal Year 2023 Budget hearing, asking the county to increase funding in the following areas:

- Expand and maintain the shade tree canopy throughout the County to reduce flooding and excessive heat impacts due to climate change, as well as improve air quality and habitat for native birds and insects. The County’s Street Tree Replacement Program is a great investment toward this request.

- Fund additional forestry positions in the Department of Environmental Protection and Sustainability (DEPS). Three additional forestry positions were created in the budget including an urban forester who is administering the Street Tree Replacement Program.

- Fund a canopy tree inventory by DEPS using GIS, based on the Downtown Towson Tree Survey created by the Green Towson Alliance and plant trees downtown. DEPS is tracking the Street Tree Replacement program with a GIS program.

- Fund a position in the Department of Recreation and Parks to administer a volunteer “weed warrior” program, like programs in Baltimore City and Montgomery County, that will organize and manage volunteer efforts for habitat restoration, particularly for removal of invasive vines that are slowly destroying our existing trees. We will continue to advocate for this.

- Create a county-wide open space plan similar to the NeighborSpace of Baltimore County initiative. We will continue to advocate for this.

INVASIVE PLANTS INITIATIVES

Green Towson Alliance volunteers have continued to remove invasive vines and plants from the Blakehurst Retirement Community property, in Radebaugh Park and Overlook Park. In parks, GTA members from nearby neighborhoods are working in coordination with the Towson Rec Council of Baltimore County Rec and Parks to remove invasive plants (Overlook Park) and plant pollinator-friendly native perennials (Radebaugh Park entrance gardens at 11 Maryland Ave).

The effects of the invasive plant removal in Overlook Park were striking:

Beneficial native plants in Overlook Park got a boost in 2022 from the dedicated volunteers of Habitat Stewards of Overlook Park (HSOP.) Habitat was restored by manually removing (without power tools or herbicides) non-native invasive plants (NNIs) that outcompete and smother natives. In addition to freeing dozens of trees from English Ivy, the group’s methodical removal of aggressive non-native Porcelain Berry vines near the athletic field and stream gave a variety of native plants access to the air, water, and sunlight they need. It was exciting to observe so many natives unexpectedly rise up, phoenix-like, as if they had been just waiting for their chance. These native plants include: Blue-eyed Grass, Blue Flag Iris, Boxelder, Black Raspberry, Common Milkweed, Daisy Fleabane, Dogbane, Horse Chestnut, Pignut Hickory, Red Chokeberry, Tall White Beardtongue, and Virginia Creeper. Beneficial native insects seen utilizing these plants include butterflies such as Azures, Eastern-tailed Blues, Monarchs, Common Sootywing and Silver-spotted Skippers, Brown-belted Bumble Bees, Red Milkweed Beetles, and Orange Assassin Bugs. Birds seen include Red-shouldered Hawks, Pileated Woodpeckers, Gray Catbirds, Carolina Wrens, and many others.

after invasive vines that had been covering it were removed.

The work at Overlook Park will begin again this month. If you’re interested in helping out, please contact Adreon Hubbard at hubbardesol@gmail.com.

Invasive plant removal at Blakehurst Retirement Community is ongoing as well. Volunteers worked through the early spring of 2022 and then paused during the summer while a professional environmental service company removed large areas of Porcelain Berry and other invasive species. Blakehurst is working with Baltimore County to re-forest at least some of these areas.

NATIVE PLANTS INITIATIVES

GTA engaged in several public education efforts to inform our neighbors about the vital link native plants and trees play in supporting our environment. This includes the Towson Native Garden Contest, which we have run for the past two years; an educational display at the Stoneleigh Elementary School Environmental Fair, the Church of the Redeemer Native Plant Sale and the Towson Gardens Day. We also arranged a tour of the green roof and rain gardens at Patriot Plaza and the Towson Fire Station which utilized native plants. We marched in the Towson 4th of July Parade promoting “Nature’s Communities” of native plants and the bees and butterflies they host.

More information on native plants and the upcoming 2023 Native Garden Contest can be found at nativegardencontest.com

2022 Native Garden Contest

COMMUNITY INITIATIVES

GTA signed on as supporters of the Road to Freedom Trail, a proposed multi-purpose trail linking Hampton Plantation to Historic East Towson. The trail is conceived as an educational, environmental, and historical trail for walking and cycling that will tell the story of the relationship between the 500 enslaved people at the Ridgely estate and the enclave of those who were manumitted after 1829 and created a community nearby in Towson.

IN ANNAPOLIS

GTA advocated for the passage of several bills in the Maryland General Assembly. The following bills passed:

- HB15/SB7 Invasive and Native Plants expands the list of invasive species regulated in Maryland. It also requires state agencies and projects with state funding to prioritize the use of native plants. – PASSED

- HB275 George “Walter” Taylor Act prohibits the use, manufacture or sale of fire-fighting foams, carpets and food containers that contain PFAS after January 2023. PFAS are Per-and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances which are a type of human made ‘forever chemical’ and a known carcinogen. – PASSED

- SB541 Great Maryland Outdoors Act Provides historic investment in Maryland’s state park system. It funds new full-time positions in the Maryland Park Service to deal with park overcrowding, addresses a long maintenance backlog, restores historic sites, fixes aging infrastructure, and acquires new parkland. It also has provisions to improve the equity of access to our state parks. – PASSED

- SB0528 Climate Solutions Now Act of 2022 This comprehensive climate bill requires the state to cut emissions 60% below 2006 levels by 2030 and achieve net-zero emissions by 2045 by addressing emissions from the transportation, building, and electricity sectors. It also promotes equity in the allocation of climate funding. – PASSED

The following bills did not get voted out of their House/Senate Committees:

- HB59/SB783 Constitutional Amendment for Environmental Human Rights guaranteeing each person in the State of Maryland the right to a healthful environment.

- HB0135 Environment – Single-Use Plastics – Restrictions to prohibit a food service business from providing certain single-use plastic food and beverage products to a customer unless the customer asks for them. The majority of these items are not recyclable and they often end up in our streams and rivers.

- HB0376 Outdoor Preschool License Pilot Program – Establishment to establish the Outdoor Preschool License Pilot Program in the Maryland State Department of Education to license outdoor, nature-based early learning and child care programs in order to expand access to affordable, high-quality early learning programs and to investigate the benefits of outdoor, nature-based classrooms.

Green Towson Alliance looks forward to another productive year in 2023. You can find us on Facebook at https://www.facebook.com/GreenTowsonAlliance and on our website at https://greentowsonalliance.org/

Towson Native Garden Contest!

Native gardens are blossoming across Towson. We know so because of the Green Towson Alliance’s wildly popular native garden contest. Last year’s first effort drew many entries and connected gardeners across Towson. I had the chance to visit several of the gardens, here, here and here, so much fun and inspiration galore!

A couple of things connected these very different gardens together. Each, whether in the back of row home on a narrower lot or a single family home on a wider lot, had a comfy space for sitting in and amongst the garden. One of the fun things about gardening with native plants is your garden comes more alive the more native plants you add. Having a place to sit and immerse yourself in it is one of the true pleasures of this endeavor.

A plant in common? All grow rudbeckia (Rudbeckia fulgida), the Maryland state flower. Yes, it is common but what a powerhouse! Early to green up, blooms July through September and then, those seed heads feed birds through the winter. It spreads on its own. It really needs no care. Grows in sun or part shade. It’s a great place to start. Why a contest? This was all a seed of an idea by Patty Mochel, a savvy media specialist by profession, and now a Doug Tallamy convert to native plants. Patty has always gardened. In her twenties she grew vegetables. She became a master gardener and added many trees, shrubs and flowers to her garden, always immensely enjoying it.

Please continue reading this article in the Nuts for Natives blog.

How to Plant a Tree

By Carl Gold

I am kneeling in the soil using my hands to fill a hole. I am dirty and my back is stiff. My fingernails are cracked and my hands are callused and rough to the touch. I have not looked at my watch or cell phone for hours. I have spent the morning planting native trees. Planting a tree is like planting oxygen. Replanting trees in urban areas that have been denuded can heal heat islands, clean the air, filter water, reduce asthma, provide habitat and raise property values. Trees shade homes in the summer and serve as windbreaks in the winter. Trees absorb carbon and ultraviolet radiation. They are first line defenders against climate change.

Early spring and early fall are the best times to plant a tree. When a tree is planted it goes into shock- hot summer weather and drought add to this stress and can kill the tree before it has a chance to adapt. Similarly, freezing temperatures prevent root growth and a winter planted tree will struggle. If possible, plant a tree native to our region. Native trees bloom and leaf out timed to match the hatching of certain insects that rely on them for food. If those insects are not around migrating birds that feed on the insects will go elsewhere. A single mature oak tree can host over 500 species of nascent moths and butterflies – more than any other plant or tree. This is a wildlife smorgasbord. An oak may take 40-60 years to mature – but can live for centuries.

The planting hole should be 2-3 times as wide as the root ball. Start by removing any grass. Save it and set it aside. Make the sides of your circular hole perpendicular to the bottom- avoid slanted sides. The bottom of the hole should be flat so that water will not pool under the tree and tilt it. If your soil is severely compacted from development or construction, consider amending it with compost or better soil and increasing the width of the hole to give roots room to grow. Low-cost compost is available from Baltimore City’s Camp Small.

Cut away any wire and burlap or remove your new tree from the plastic pot. Now you must act ruthlessly and counterintuitively. If your tree grew in a plastic pot, it is highly likely that the roots are encircling the tree and if not addressed will ultimately girdle and kill the tree. Use a knife or your fingers to release the circling roots- it is ok to cut them to do this. If any of the roots have woody portions that are growing back towards the trunk- cut them off! They will never change direction so they must be removed to protect the tree from itself. Next, find the tree flare or first structural root- this is where the trunk widens at the base of the tree. It is likely to be covered with soil that you will have to remove. Planting depth is crucial. The tree flare must be visible just above the surface once you fill in the hole- it is better to be an inch too high than an inch too low- the tree will settle as you water it. The easiest way to make sure the depth is correct is to lay your shovel across the hole as you are back filling from the soil you set aside. The root flare should be level with the bottom of the shovel handle or slightly higher. If you are working solo, stop and check that the tree is centered and straight. Take the grass you removed, flip it over and create a berm around the tree. Cover with mulch making sure to leave the flare exposed. Think doughnut, not volcano.

From March to October, water your new tree at least weekly the equivalent of one to two inches of rainfall for the first two years. You might want to stake it to protect against lawnmowers and weedwhackers. If deer are a problem, you can wrap inexpensive fencing around the stakes to protect the tree. Depending on how bad the deer problem is you may need to keep the fencing for several years.

You have now given all of us a gift that will surpass anything you could do in your will.

Carl Gold is a Maryland Master Naturalist and a certified weed warrior and tree keeper. He can be reached at cgold@carlgoldlaw.com.

Silent Spring – A voice still ringing

by Carey Murphy

“In nature, nothing exists alone” – Rachel Carson

Sixty years ago, Rachel Carson opened her landmark book Silent Spring by imagining what a world without singing birds and chirping insects would be like. Then she warned us we were heading there. This classic exposé on chemical pesticides inspired a new environmental movement that helped to launch the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. The book languished on my shelf, unopened for 20 years, likely because I knew it wouldn’t be easy reading. I also assumed it would be a record of what was.

I was surprised that much of the book reads like a journal entry of what still is.

“What the public is asked to accept as ‘safe’ today may turn out tomorrow to be extremely dangerous.” – RC

Carson laid bare just how interconnected life on earth is. In clear yet evocative prose, she describes how efforts to manage unwanted insects and plants with synthetic chemicals lead to unexpected environmental devastation and damage in our human bodies. Ironically, the expensive and deadly programs to combat fire ants, spruce budworms, and weeds in the middle of the 20th century proved ineffective. Today we still generously apply toxic chemicals without registering the consequences. The DDT, dieldrin and other pesticides Carson warns about, which have since been banned, have been replaced by others just as harmful. For instance, neonicotinoids linger inside plants and soil for years continuously poisoning bees and other insects; while pyrethroids frequently used in mosquito sprays are known to severely damage aquatic environments. (Both of these substitutes are suspected of affecting human health as well.) The most widely used herbicide of all, glyphosate, just now faces its day of reckoning, though it’s been on the market since 1974. Another ubiquitous herbicide Carson cautioned about, 2,4 D, is still commonly used by contractors and as part of DIY “weed and feed” combos sold at local hardware stores. (“Pesticides” is an overarching term that includes herbicides, insecticides, fungicides, rodenticides, etc.)

Carson is pragmatic and she doesn’t argue for the complete stoppage of pesticides. Sometimes targeted treatment is our best course of action to manage insurgent invasive weeds or to protect crops or prevent transmission of disease, but we often use them indiscriminately. And sometimes we are trapped, as in the “pesticide treadmill”of industrial agriculture; we pour more and more chemicals directly on our food crops in an effort to one-up the ever-evolving superweeds.

“Man is more dependent upon these wild pollinators than he usually realizes.” – RC

there would be no monarchs.

Our overuse of pesticides is implicated as the main driver of insect decline, which is now exacerbated by a changing climate, habitat loss and invasive species. Over the last 50 years, global insect numbers have dropped by an estimated 75 percent with some species faring worse than others. For instance, butterflies and moths have decreased by over 50 percent across the globe. Most of us know the plight of our monarch butterfly; its numbers have plummeted over 80 % since the 1990s.

Because insects are necessary for the food chain, for pollination of natural plants and agricultural crops—well, for life as we know it—it behooves us to start paying attention to their dwindling presence. My best friend in high school had a joke back in the early ’90s that involved bugs landing on her windshield: “I bet he’ll never have the guts to do that again!” It’s probably not something one thinks about much these days, but the windshield phenomenon, as it’s called, is real. I haven’t been able to recycle that joke in a long time, as we are no longer scraping bugs off of our cars.

“Instead of treating the basic condition [of the soil], suburbanites- advised by nurserymen who in turn have been advised by the chemical manufacturers – continue to apply truly astonishing amounts of crabgrass killers to their lawns each year.” – RC

Winter is a time of great hibernation for insects and seeds like crabgrass. But all too soon, the chemicals will again reign supreme, or at least try to. I will get the knocks on my door from the Aptive salesmen who try to peer pressure me into killing all the beneficial spiders around my foundation; they will spout off the neighbors who have already enlisted. The Trugreen guys will wave their magic hoses over the lawns and common areas throughout the neighborhood to kill crabgrass and other “weeds” and the Mosquito-spraying trucks will cruise the streets. The little yellow caution signs will crop up throughout my neighborhood. I will again document dead bees and make sure my windows are closed to the inevitable drift.

We spend over $10 billion annually on pesticides in the U.S., yet if we factor in the costs to our health and the environment, the tab is actually much higher. Before the advent of manufactured chemicals, cancer wasn’t common. But as Carson discusses in Silent Spring, after the introduction of chemical pesticides in the 1940s, 1 in 4 people were diagnosed with cancer. It had also become the number one disease killing children – which was basically unheard of until then. In the 21st century, our odds are now 50% of developing cancer in our lifetimes. All of us have traces of pesticides in our body mingling among other damaging chemicals like PCBs and PFAS, often times lying in wait in our livers. Pesticides cross the placenta and are common in breast milk affecting the most vulnerable: our developing infants and children. Pesticides show up in our drinking water and in our Cheerios. Not surprisingly, pesticides are associated with asthma, autism and learning disabilities, birth defects and reproductive dysfunction, diabetes, Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s diseases. The risk to our pets is also high.

“Responsible public health officials have pointed out that the biological effects of chemicals are cumulative over long periods of time, and that the hazard to the individual may depend on the sum of the exposures received throughout his lifetime. For these very reasons the danger is easily ignored. It is human nature to shrug off what may seem to us a vague threat of future disaster.” – RC

But rarely does this information make it to our inboxes or even mainstream news. And, if it does, we often ignore it like other warnings that seem too far off into the future, such as climate change. So when lawn care companies tell us that pesticides are “non-toxic” and advertisements suggest they are healthy for the earth, we believe them. We look for the simple fix to be compliant with our HOAs and to keep up with our neighbors. Well-meaning folks have told me herbicides are safer than pesticides and that companies wouldn’t dare use anything that would harm the people applying them. Though let’s not forget those occupational hazards that exposed people to asbestos, radium, and now Roundup. In reality, everything with a “cide” in its name is designed to kill.

In an interview (because the book is a whopping $135, I haven’t read it), the editors of Herbicides: Chemistry, Efficacy, Toxicology, and Environmental Impacts (2021) raise some pointed concerns and questions, which should be considered by our decision-makers. This, keep in mind, is 60 years after Rachel Carson sounded alarms:

Another key message is that every herbicide carries risk. Contrary to a widespread assumption, herbicides not only kill weeds but have direct and indirect impacts on a wide variety of non-target organisms and the function of ecosystems. Safe use requires definition of an acceptable level. Weighing the risk-benefit ratio involves toxicological, economic, social, and environmental considerations… As an ecologist working on climate change aspects, I long ignored the issue of herbicides (and pesticides in general). I simply thought that there is not much to research because those substances are rigorously tested before they are released into our environment. Then, after diving into the huge body of literature I realized that many studies lack a holistic perspective, including interactions between species, between different substances applied in the fields, ethical and socioeconomic aspects. Since then I have tried to ask what is behind bold statements about the necessity and harmlessness of pesticides: Is there a possible conflict of interest? Have some aspects been forgotten or ignored? Are alternatives considered at all?

I, too, didn’t learn until recently that pesticide manufacturers conduct their own research to determine “safe” levels and that inert ingredients are “trade secrets” that aren’t required to be tested or included on labels. Yet, in at least one study, researchers concluded that 8 out of 9 formulations of Roundup were “up to one thousand times more toxic” than the main ingredient glyphosate. And this eye-opening Intercept article last summer revealed that many EPA scientists have gone on to work for the pesticide manufacturers. The author writes: “the enormous corporate influence has weakened and, in some cases, shut down the meaningful regulation of pesticides in the U.S. and left the country’s residents exposed to levels of dangerous chemicals not tolerated in many other nations.” Over 70 pesticides still in use in the U.S. today are banned by the EU and other nations.

Some cities and communities across the country are taking a stand where they can. Our next door neighbor, Montgomery County, Maryland, recently banned the use of pesticides for aesthetic purposes for private lawns, playgrounds and other places where children play citing serious health risks. Lawn care companies, as a result, now offer organic land care alternatives. Rachel Carson, who wrote Silent Spring from her home in Montgomery County, would be proud of this evolution—even if decades late.

“…we have at last asserted our ‘right to know’, and if, knowing, we have concluded that we are being asked to take senseless and frightening risks, then we should no longer accept the counsel of those who tell us that we must fill our world with poisonous chemicals; we should look about and see what other course is open to us.” – RC

Maybe 2022 will be the year we heed the message from Silent Spring and ditch the chemicals we do not need. We could recognize instead that healthy soils help prevent unwanted plants. Maybe we could allow—like in times past—the clover and violets to grow a bit here and there. These “weeds” would certainly provide a much-needed food source for pollinators and allow butterflies like the great spangled fritillary to produce another generation. We could stop dousing the sides of our highways with chemicals and let meadow plants regain their foothold. We could certainly skip the irrigation systems that spray for mosquitos on a timer. We could support our local farmers, especially those who practice sustainable agriculture. We could increase biodiversity, decrease greenhouse gas emissions (it takes a lot of energy to create synthetic pesticides and fertilizers), and minimize flooding. If we use regenerative practices on our turf lawns, we could even draw down 20 times more carbon in the soil than a typically managed one.

We could let nature get back to the business of balancing itself.

This past year while serving on the Grounds Committee in my neighborhood, I have often

raised concerns regarding the routine use of pesticides. On much of our common spaces and townhome properties, herbicides and synthetic fertilizers are applied throughout the year, and sometimes without proper notice to residents. Now available on our HOA network are the Safety Data Sheets of the herbicides used—all of which have a warning, including: “known carcinogen” or “suspected of causing cancer,” or “may cause damage to organs through prolonged or repeated exposure” or “very toxic to aquatic life”. I’m grateful that our Committee and Board agreed recently to allow townhome properties to opt-out of the chemical treatments and to explore options for organic turf management on our common HOA property, including the fields where children frequently play.

Solutions do exist!

To aid in the transition away from harmful lawn chemicals, Green Team Urbana has developed a presentation on the basics of providing a healthy yard for families, pets and wildlife. We discuss how to build healthy soils, care for grass organically, and create new opportunities for wildlife as a result of Maryland’s new low-impact landscaping law. It is possible to have a nice lawn without the use of pesticides.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

Beyond Pesticides has been protecting health and the environment with science, policy and action for 40 years.

Non Toxic Communities includes links to advocacy training and how to start a pesticides awareness campaign.

The Environmental Working Group aims to empower consumers with breakthrough research to make informed choices and live a healthy life in a healthy environment.

Visit their website and check out their consumer guides, including: Dirty Dozen, Skin Deep and Tap Water Database.

Best practices for an organic lawn: Paul Tukey on Saving the Earth, One Lawn at a Time – courtesy of Interfaith Partners of the Chesapeake.

How to Avoid Greenwashing and Harmful Chemicals in Lawn Care includes tips on how to read a Safety Data Sheet and how to research lawncare companies.

Attack of the Superweeds by H. Clair Brown in The New York Times (8/18/21)

EPA Plans to Clean Up Troubled Chemical and Pesticide Programs by Sharon Lerner in The Intercept. A follow-up to her series: EPA Exposed. (10/14/21)

This article was originally published by Green Team Urbana, a volunteer environmental group in Frederick County, and reprinted here with their permission. You can find the original article here.

Can the Soil Seed Bank Save Us?

By Nathan Lamb

Imagine two woodlands. Both have deciduous, fire-adapted trees overhead (mostly oaks and hickories). One has widely spaced trees, and sunlight reaches a diverse community of grasses, sedges, and forbs. The other has a dense thicket of shrubs (primarily introduced buckthorn, Rhamnus cathartica) that makes walking difficult and shades out all but the earliest spring ephemerals. Now imagine you want to turn the shrubby woodland into a sunny one. If you remove the shrubs, will the light that reaches the bare soil trigger a profusion of native plants, restoring the diverse community that lived there hundreds of years ago?

There are occasional, exciting success stories, and the appeal of the soil seed bank regenerating the landscape is understandable. If restoration practitioners and ecological gardeners can count on the soil seed bank, they can spend less time collecting and sowing seeds. There’s also a desire for authenticity and continuity. If the soil does contain species that were present before Europeans stopped millennia of indigenous stewardship, then the restored community will be much more resilient and appropriate to the site. Another philosophical question hovers around the edges: does nature function best when people clean up their messes and get out of the way, or when they take a more active role?

Planning for Success

The problem is that it’s hard to guarantee success when relying on soil seed banks. How can we know that the plant community that germinates after we remove a buckthorn tangle will be one that we want, not just more buckthorn or garlic mustard or another headache? Research suggests this technique can help restore wetlands because those plants evolved with scouring floods, and the longevity of buried seeds is crucial. It doesn’t generally work for prairies, partly because plowing and other disruptions introduced by European settlers have depleted soil seed banks and partly due to the nature of prairie plant communities. Prairies go through successional stages as they develop, and the weedier plants of the earliest stages are the most likely to survive in the soil and recolonize after a disturbance. Whether the soil seed bank can help restore deciduous woodlands is less understood.

In 2016 I was a graduate student at the Chicago Botanic Garden, where, with scientists and staff, I studied woodland soil seed banks to help practitioners make difficult restoration decisions. In the Chicago region, volunteer land stewards with groups like the North Branch Restoration Project have spent countless hours over the last 40 years restoring oak woodlands and spearheading much of what we know about ecological restoration in the Midwest. The preserves they care for are beautiful and serve as essential habitats in an urban area. In and around the city, these woodlands have a history of fragmentation and fire suppression that has encouraged the proliferation of woody shrubs like buckthorn. The still unrestored sites are a good stand-in for suburban, fragmented woodlands throughout eastern North America, which are prime targets for restoration.

Testing Results

We wanted to answer the question: what would happen if we removed buckthorn and other introduced shrubs and allowed the soil seed bank to germinate without sowing additional seeds? We wanted to characterize the plant community that would show up in the crucial early years of restoration. To begin, we paired unrestored woodlands (no history of shrub removal, seeding, or prescribed burning) with restored woodlands (more than ten years of shrub removal, seeding, and periodic burning). Ideally, we would have used a reference community (an ecosystem that’s remained relatively unchanged since before the European invasion) instead of a restored woodland, but land management changes are so widespread in this region that there are few unaltered woodlands left. We surveyed nine unrestored and nine restored woodland plant communities within the Forest Preserves of Cook County. From each, we took two soil seed bank samples that we germinated back at the Chicago Botanic Garden.

Our germination protocols were low-tech and could be replicated with nursery flats and some seed starting mix:

- Clear leaf litter from a 20cm x 20cm patch and bag it to sieve for seeds later, then collect soil to a depth of 5cm (seeds buried deeper are unlikely to reach the surface during restoration, and seed survival declines with depth).

- Sieve samples using fine mesh soil sieves or a colander, saving any large seeds that you see. Collect the soil and seeds that fall through and dispose of woody debris and plant matter that remains.

- Mix each sample with water to form a slurry and pour into 40 cm x 20 cm trays on top of 4 cm of seed starting mix.

- Spread a thin layer of vermiculite over each to encourage the germination of seeds that may have floated to the surface but require darkness to germinate.

- Include “control” trays containing only seed starting mix to measure any wind-borne seeds that disperse into the nearby trays.

- Water regularly using a mist nozzle to avoid disturbing seeds or young seedlings.

- Record and remove seedlings as soon as they can be identified. Difficult-to-identify seedlings can be potted up to encourage growth and flowering. The Tallgrass Prairie Center Guide to Seed and Seedling Identification is a good resource, and your local natural heritage program or botanic garden may be able to provide additional assistance.

By every metric we tested, unrestored soil seed banks were far less diverse and bore little resemblance to the aboveground plant communities of restored woodlands. This means it’s unlikely that a soil seed bank would produce the diverse plant community that is the target of a restoration project. Unless a germination test indicates otherwise, supplemental seeding is probably necessary to achieve restoration goals. In our tests, the most abundant species of unrestored soil seed banks were buckthorn and early successional species like Juncus tenuis (path rush), Potentilla simplex (common cinquefoil), and Solidago canadensis (Canada goldenrod). Species in restored soil seed banks were more likely to have a high coefficient of conservatism, a measure of habitat specificity and sensitivity to disturbance, and included woodland grasses (Cinna arundinacea, Brachyelytrum erectum), sedges (Carex hirsutella, Carex squarrosa), and forbs (Symphyotrichum drummondii, Solidago flexicaulis).

Evaluating Results

Interestingly, there was no difference in the number of non-native seeds between restored and unrestored soil seed banks, but restored soil seed banks had nearly three times as many native seeds. This means there is not a disproportionate number of non-native seeds waiting to take over, but there is a lack of native seeds available to compete. The long history of grazing and plowing these spaces may have eliminated the soil seed banks of native plant communities, leaving an open niche that was filled by buckthorn when the land was abandoned by farmers. Returning seeds to the soil through active stewardship is, in effect, rebuilding the land’s resilience.

About the Author

Nathan Lamb is an ecological garden designer and consultant living in southern Rhode Island. He worked in stream and wetland restoration, field conservation, and public horticulture before getting an MS in Plant Biology and working as Assistant Director of Heronswood Garden in Washington. Now he helps people grow resilient gardens that support wildlife, require fewer inputs, and evoke the beauty of wild nature. He can be reached through www.gardenecology.us. This article was published by Ecological Landscape Alliance and reprinted with permission.